Influencer marketing is a popular strategy for brands seeking to engage consumers on sites like Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. But as Geoffrey Precourt, WARC's US Editor, found in a debate between two of the biggest names in American journalism, this activity – and the attendant debates regarding ethics, transparency, and disclosure – are far from new.

Each generation of marketers would like to think it has reinvented the way that messaging brings brands and consumers closer together.

But Charlie Chappell, head/integrated media and communications planning at the Hershey Co., for one, believes that the phenomenon of social media, and the marketing influencers it has spawned, are just new spins on old tricks.

“All through humanity,” he told a recent conference held by the Association of National Advertisers (ANA), “people have wanted to engage with other people. What technology has done is scale that onto a massive level.”

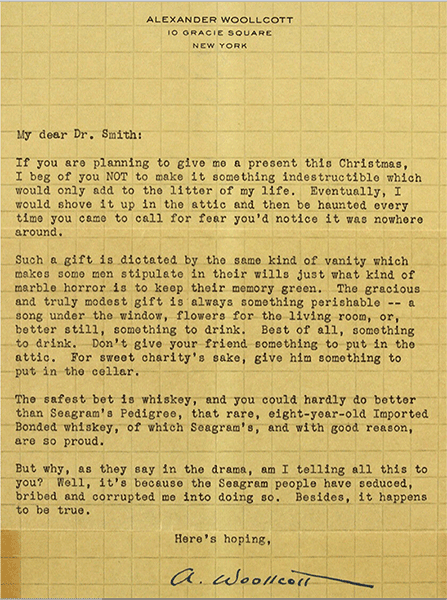

Alexander Woollcott

Evidence: Eighty-three years ago, Alexander Woollcott was a Kardashian-level force of culture in New York literary circles. In 1909, a spanking-fresh graduate of Hamilton College, Woollcott joined The New York Times as a cub reporter; by 1914, he was the paper’s drama critic. Five years later, he was one of the founders of the Algonquin Round Table, a festive, snarky set of New York writers who were a spout of Manhattan culture (and humor) for the next decade, leaving behind an iconic culture of literacy elan that would survive into the next century.

In the Christmas season of 1936, Woollcott decided to cash in on his profile – and panache – when he accepted an offer from Seagram’s, at the time the world’s largest owner of alcoholic beverages, to be an influencer.

By that time, he had finished five years as The New Yorker’s “Shouts & Murmurs” critic/essayist, and his address book had never been thicker or richer. The deal was simple: Woollcott would greet scores of friends a with typewritten holiday letter that entreated:

“If you are planning to give me a present this Christmas, I beg you not to make it something indestructible which would only add to the litter of my life. Eventually, I would shove it up in the attic and then be haunted every time you came to call for fear you’d notice it was nowhere around...

“The gracious and truly modest gift is always something perishable – a song under the window, flowers for the living room, or, better still, something to drink. Don’t give your friend something to put in the attic. For sweet charity’s sake, give him something to put in the cellar.

“The safest bet is whiskey, and you could hardly do better than Seagram’s Pedigree, that rare, eight-year-old Imported bonded whiskey, of which Seagram’s, and with good reason, are so proud.”

The original letters today are scattered all over the internet at various literary-auction sites. (You can have one of your own at bids at start around $295)….

… and part of their value rests in their whimsical honesty: unlike the current generation of influencers, Woollcott offered full disclosure of his brand association: “But why, as the say in the drama, am I telling you this?” he concluded one letter after another.

“Well, it’s because the Seagram people have seduced, bribed, and corrupted me into doing so. Besides, it happens to be true.”

That touch of integrity did not impress E.B. White, Woollcott’s New Yorker colleague. (In addition to his “Shouts & Murmurs” contributions, Woollcott wrote for the magazine on and off between 1925 and 1938.)

White remains one of the brightest literary lights of his time and, as a writer/editor, guarded the publication’s moral groundings in “Talk of the Town” pieces, essays, and occasional contributions of conscience that appeared under the byline of “Eustace Tilley”, the fictional dandy who graced the magazine’s first cover, and still remains part of its cultural zeitgeist.

E.B. White

Even as White was very much a part of the soul of the magazine, he distinctly was not part of the Round Table culture. In fact, by the late 1930s, he was living in a farmhouse far up the coast of Maine, and mailing in his New Yorker contributions.

And one such contribution arrived in time for the December 19, 1936 issue, where a letter from Tilley appeared under a copy of the Woollcott/Seagram’s note:

“About your request that we give you some Seagram’s eight-year-old imported bonded whiskey for Christmas, we’re sorry but it’s out of the question. Our gift to you is all bought, all wrapped, ready to go by Western Union Messenger to your home on Gracie Square. We have instructed the messenger just to look for a radiance in the sky, and follow it.

“Our gift, we are sorry to say, is indestructible. It is a tippet [a long scarf or shawl worn around a woman’s neck and/or shoulders], lined with burrs. The tippet we got at Bonwit Teller’s, the burrs we picked ourself. It is depressing to us to learn that you eventually will ‘shove it up in the attic,’ but many Christmases have inured us to the disappointments of giving and receiving...

“The holidays come and go, yet this Christmas of 1936, thanks to your thoughtful note, has been given an unforgettable flavor pervaded with the faint, exquisite perfume of well-rotted holly berries.”

It would seem that the business side of the weekly magazine jumped into the exchange. The two letters appeared in a single center column on the left side of the page. Surrounding the editorial copy was a sea of advertisements for Seagram’s competitors.

Facing the item was a full-page ad for a Scotch whiskey; adjacent were fractional ads for a Jamaican rum and Otard Brandy (a Schenley Industries import from France that’s now a subsidiary of the Bacardi group) that carried, properly within its bodycopy, a ditty from Ogden Nash, yet another New Yorker contributor: “Her guests were the crème de la cream/so they stifled their impulse to scream/And they weathered the siege/By noblesse oblige/And Otard, the cognac supreme.”

A 21st-century Kardashian might have turned the other cheek and not rebutted such a rebuke from White. But Woollcott complained to the New Yorker management. White responded:

“Serving the New Yorker in my capacity as jackanapes of all trades, I sometimes discover myself in the act of muddying up my friends and acquaintances – as in the case of you and the Seagram letter. I always throw myself into these discourtesies with a will, dreamily hoping to achieve heavenly grace through earthly impartiality. My wife [the magazine’s fiction editor] tells me you are convinced we maintain a Dept. of Animus; but my true belief is we have as little animus as is consistent with good publishing. In which case, my own animus, if any, was against the frantic society to which we all fall victim, in varying measure.”

A week later, a written response from Woollcott in hand, White was less kind, “emboldened to write this long, smug-sounding letter, full of how wonderful and right I am and how terrible and wrong you are, first because you asked for it, but more because the persons who have spoken to me about your endorsement have, almost to a man, seemed to feel either offended, shattered, enraged, or just plain startled.”

He continued:

“In your letter, you mention honesty and dignity. I don’t think endorsements are necessarily dishonest (certainly your letter spoke plainly enough) and I don’t give a whoop about dignity...

“When you, full of an idea, engage to write a piece for a publication, write it, and get paid, you are performing a literary or creative act and are being paid for the results of your talent and labor.

“When you, again, full of an idea, write an advertisement for Seagram on your letterhead, what you really are selling is the name Woollcott, which is valuable to a commercial house because you had previously established yourself as a vivid person who could write and who was interesting to many people.

“Now, as one of your readers or as one of your acquaintances, or both, or neither, I object to your addressing me by way of a liquor house in whose debt you are. I feel patronized, and you seem suddenly discredited.”

In that same note, written on Christmas Eve 1936, White addressed what would become a hot point for generations of writers, artists, athletes, and brands:

“I still cling (by my teeth these days) to the notion that writing is a trust, that you were born in Phalanx not as other Phalanxians but with a star over your head and an itch to get going ... Then, in the midst of your writings, comes a letter … saying that you like Seagram’s whiskey.

“The next time I come across you, in the mail, in print, I feel must be on my guard, must see what the catch is, may have to read half-way through before I can determine whether this is an affiliated utterance or an unaffiliated utterance...

“This, in my opinion, dissipates a man’s character, destroys a writer’s credit.”

Those rules still abide. But, as Hershey’s Charlie Chappell points out, the scale is much larger and the consequences – favorable or not – much higher.