At an event in central London, strategists gathered to borrow skills from sister professions in order to make them better students of the human. Here’s what WARC’s reporter learned.

Many planners grow – or fall – into their strategic roles, being spotted for talent and aptitude rather than qualifications. And while many are clearly doing their jobs well, there’s a constant anxiety about what their peers are up to. One consequence is that planners tend to end up fishing in the same pools.

How does a planner escape from their pool? Mostly, with new ideas from different disciplines and from other professionals whose subject is the same as theirs: the human being and their flawed desires. At an APG Noisy Thinking event (London, April 2018), four practitioners outlined new ideas on exploring different pools.

The mathematician

In the current climate, data-driven insight has an increasingly bad name. Not only, joked Alex Steer, Chief Product Officer of Wavemaker, because “it’s a bit speccy”, but because data people in media agencies have become the most evil people in the world – a remark accompanied by an image of Cambridge Analytica’s Alexander Nix looming on the screen behind him.

Data, like machine learning and blockchain, is the future – that much we know. We also know it’s the ‘new oil’ and we also know the sensation of boiling anger when somebody repeats such a bland observation.

“There’s no shortage of people talking about data,” Steer observed, “but there is a shortage of people talking about the underlying maths of advertising.”

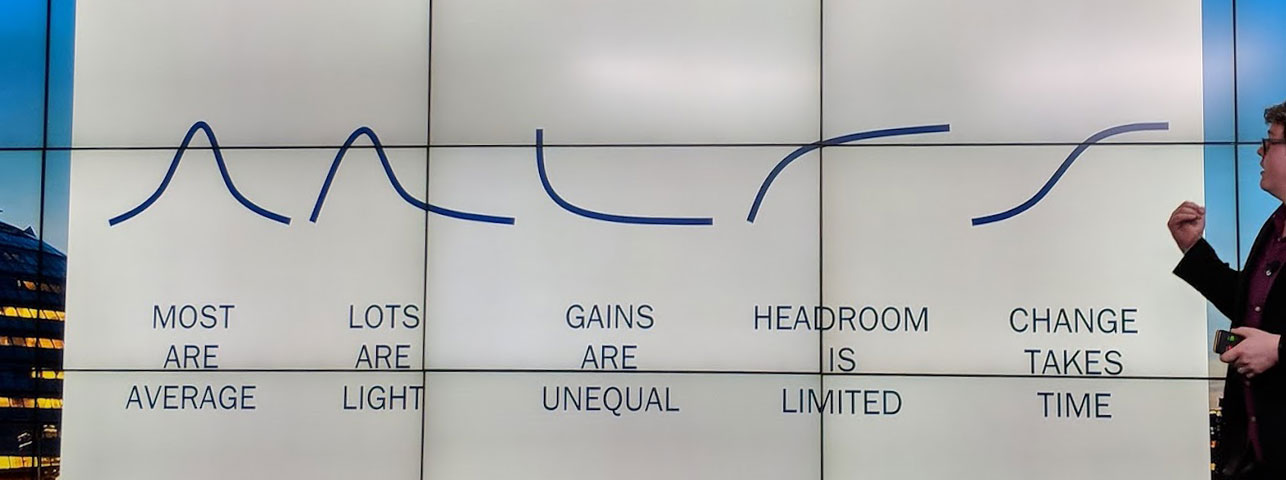

This is more likely to form basic rules rather than the granularity of data that has become today’s currency, but these underlying patterns are important, because they are the odds you have to beat in order to create great work and get a ticket to Cannes. “You need to know the odds in order to beat them,” Steer pointed out. Here they were, from left to right:

- Normal distribution: “it’s everywhere,” and tells us that “most of you are somewhere in the middle”. It is also a good indicator of the quality and effectiveness of most advertising, which is to say unremarkable.

- Beta distribution: this describes “how much time people spend using media”.

- Negative Binomial Distribution (of Byron Sharp fame): the most famous distribution in advertising is one of the bluntest – as Steer put it, “the winner takes most distribution” – which describes how many people and how often people buy your brand.

- Cumulative binomial distribution: “how many people will see my ads,” also the sales response you get from ad-spend.

- The S-curve: How trends build in a population over time.

The trendspotter

George Webster is a futurist, whose job, as part of Flamingo’s futures team, is to spot broad cultural trends from individual moments of seeming oddity.

His example: “poop-doping”, or the idea that you can ingest someone else’s poo and it will make you better. Obviously, this is a Californian thing.

By itself this is not really a cultural trend, or not one of use to a planner. What it does, however, is serve to indicate a deeper tremor. Only by zooming out can this be seen for what it is. Somewhere between runners, self-improvers, and forward-thinkers this trend may be identified as a manifestation of two interactions: that of the cult of the individual and its modus operandi, self-quantification. While poop-doping could fall into the well-documented biohacking movement, a more interesting take, Webster suggested, might be to think of sustained-optimisation.

The digital forensics expert

To do this, Webster needed to look more broadly. He enlisted the help of Lucas Galan, a specialist in digital forensics also at Flamingo. Through linguistic modelling, which dives into the language and links between topics that users are interested in, Galan is able to map ideas and cultural trends to a much more granular level.

In one telling example, he explored runners’ conversations, five million of them, in order to arrive at a map of their ideas, fears, interests, problems, and – inevitably – injuries. Combining the indicator potential of Webster’s poop-doping observation, such a map can illuminate the origins of such an idea, allowing you to “find the layer of cultural meaning” that informs it.

Beyond that, Galan has worked on digital tracking, a deep dive into (informed and willing) individuals’ digital habits both physically and chronologically. “By getting really close to a human’s data,” he said, “we can get very close to understanding them.” The result is an ability to understand the audience as quickly as possible, Galan added, and to be able to converse with enthusiasts in a way that feels as genuine as possible.

The ethnographer

In 2006 Dr. Adam Gill went to Venezuela to do cultural research, before coming back to the UK to found Beyond Insights, “a deep human insights” agency, which draws heavily from Gill’s background in anthropology. If you want to know about humans, you’re in the right place.

Gill’s method of ethnography sat well with a room that responded pretty much unanimously in the affirmative to the question “who here is nosy as f**k?”

While the techniques of ethnography are well known, Gill suggested that it is fundamentally about desire. What’s more, the advertising that fails does so, he believes, by not understanding the kind of desires people harbour, or the qualities of the connections they so crave. He suggested five easy steps:

- Take a notebook everywhere – “if you felt it, it’s likely someone else will feel it too”.

- Get culture-shocked more often – “nothing good comes from a comfort zone”.

- Observe more – “I love to eavesdrop on people’s arguments”.

- Take more photos – the best ideas come from random information.

- Speak to more people.

The creative semiotician

“Semiotics can be confusing for people,” said Chris Arning, founder of Creative Semiotics, but “it’s a way of making explicit what we all do naturally”. In many ways, this is a formalisation of the job of planning, which is working backwards from a commercial or communications problem toward the cultural codes through which we can communicate.

But planners are vulnerable to these codes just as they seek to use them. Arning suggested that they should always try to maintain a veneer of self-reflexivity, an awareness that we are all the product of our culture and of our biases, the result of a fast-evaporating interface between our minds and machines.

So what do they tell us about planning?

Planning is interesting precisely because all of these disciplines feed into the work of the planner. It is their job to be alive to the new and the weird, to put some evidence behind it and make decisions, but still, few people outside the discipline know what a planner does or that such a job even exists.

I spoke to a woman who said that before becoming a strategist, she had no idea such a job existed. This is a failure of the industry: when we talk about planning, we need to talk about humans, and we need to talk to more people who are interested in people.