Professor Karen Nelson-Field, founder of Amplified Intelligence, joins WARC with a new bi-monthly column, Attention Applied, beginning with fresh research into the shortcomings of time-in-view as a predictor of active attention and long or short-term outcomes.

A stern reminder to stick to the basics

We were recently reminded that reach-based planning is the basic premise to brand growth. In theory I agree, but audience measurement error under the surface of impression delivery significantly reduces its ability to work. If current reach-based planning worked, each impression would achieve 100% attention volume. This would mean that 100% of the impressions you buy are watched by 100% of the audience for 100% of the time-in-view you pay for. But that is a fanciful ideal.

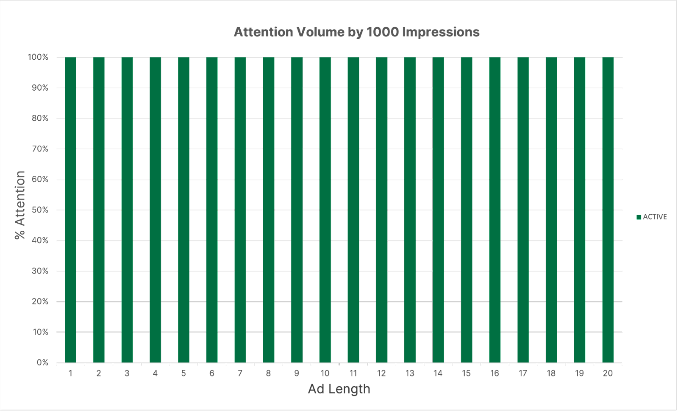

The reality looks more like the below. The first diagram below demonstrates 100% attention volume where, for each second of time-in-view, 100% of the audience looked at the ad. The second one below shows the reality of how humans interact with advertising. In this example, due to diminishing attention over time, only 44% of the reach volume you think you are buying is achieved.

To make matters worse, there are further discrepancies at the platform level. Attention volume changes significantly by media platform and format, depending on the shape of the attention decay, which makes this error very complicated to equalise. If the underlying error was the same across media types, it would be easy to fix with generic attention units, indexes or averages, but you can’t because it’s not.

But this is just the beginning of this story.

Fig 1. 100% Attention Volume versus 44% Attention Volume

The fatal gaps in time-in-view

The reason this performance error happens is not due to fraudulent publisher practices but rather because humans get distracted and don’t look at advertising in any sustained or concentrated way. While advertisers might expect this now, given the great deal of commentary on lack of human attention to advertising, the underlying and significant flow-on effects of this error are what most advertisers don’t truly grasp.

The heart of the problem is this: viewers switch frequently between attention and in-attention across the entire time an ad is on the screen, yet time-in-view quite literally doesn't account for such natural human viewing behaviour. Put another way, when a human is not looking at the ad, but the time-in-view counter is ticking, gaps appear in measurement.

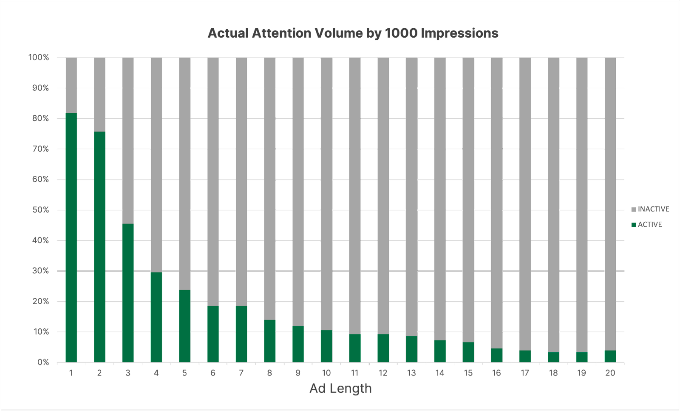

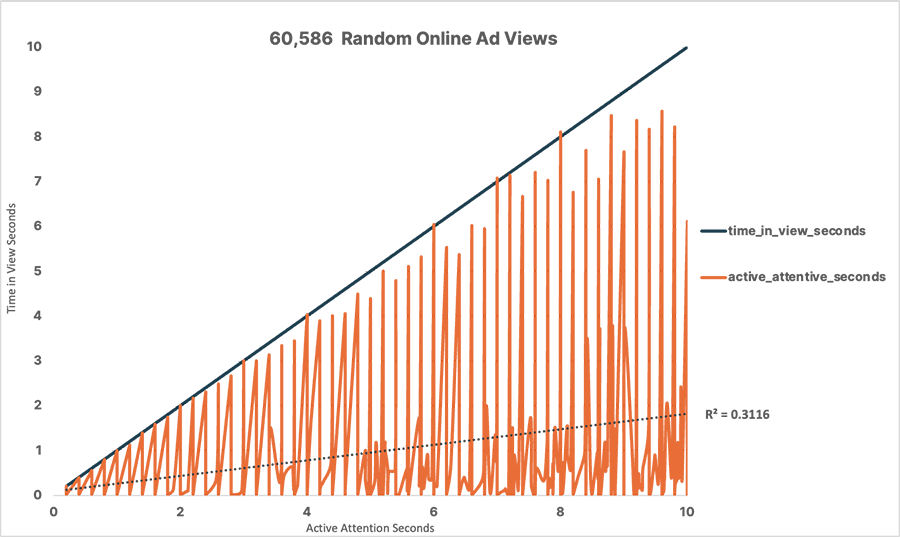

Let's look at the data for verification. The diagram below depicts findings produced after analysing a random sample of 60,000 typical online ads. Across the first critical 10 seconds in the life of an ad, you can see that less than a third of its time-in-view can be accounted for by human attention. This relationship gets worse, not better with more time-in-view, which is the exact opposite of ‘cost per completion’ type success metrics.

And, in the spirit of attention science, we recently repeated the test 28 times on broader data to secure these findings before reporting them. We looked at new data and multiple combinations of: time-in-view, active attention plus long and short-term outcomes (including brand choice and mental availability).

The findings are quite striking, yet not unexpected given what we already knew:

- Time-in-view does not predict human active attention and does not predict long or short-term outcomes.

- Human active attention data has a causal relationship with attentive time-in-view and can predict long and short-term outcomes.

Time-in-view is the inner core of modern media measurement and its failure affects reach-based planning, as well as any metrics or models that use completion rate. Plus, it is the core reason viewability measurement is critically flawed. The independent variable here does not effectively measure what we think it does, and is the root cause of large scale system failure.

Fig 2. The reality of the relationship between human attention and time-in-view (10 seconds time-in-view)

At what point did measurement fail us?

The answer to this is simple and common sense. Media measurement started to fail us when we stopped measuring ‘outward’, and started to measure ‘inward’. Remember we used to look outward to measure how humans viewed and interacted with media (even if only through rudimentary surveys), but now we only look inward to collect metadata that makes (wrong) assumptions about human viewing.

This is why attention proxies that are largely based on, or optimised towards, time-in-view don’t work. And it is these wrong assumptions that have crippled our media trading currency. Today buying and planning media has become a lottery, a dice roll.

But what does work is a combination of both inward and outward facing data, which can equalise this error.

Tools have emerged for buying and verification that use impression level meta tags but are trained on real and continuous human attention data. Acting as triggers at the point of transaction or in flight, they alert you to which impressions will achieve, or have received, more/less attention. And there are tools for planning that allow you to weight your media plans in advance of trading, using real human attention distributions in parallel to traditional reach curves.

Be mindful, though: attention commercialisation is in land grab, so watch for models that claim attention but have little to no access to human training data. For these models, when there is underlying variation in their capacity to predict human attention in the first place, it will compound error and the model’s predictive quality will get worse not better. Ask for transparency from your attention provider.

We can course correct

Ask yourself whether under any other circumstance you would agree to incorporate metrics into your organisation's critical processes knowing they are likely to output upwards of 70% error? If the answer is no, you should review any advertising practices that rely on time-in-view alone to tell you how humans behave.

Then we can all go back to reach-based planning with confidence, and not need any more reminding of its value.