Cathy Taylor, WARC’s US Commissioning Editor, introduces the latest installment in WARC’s Spotlight Brazil series, explaining how – despite current volatility and uneasiness over the coming presidential election – Brazilians have optimism about the future, even beyond the World Cup.

This article is part of the September 2022 Spotlight Brazil series, "How consumers are responding to volatile times.” Read more

The theme of the September 2022 WARC Spotlight Brazil, “How consumers are responding to volatile times” speaks to the present state of Brazilian consumers, but it’s something that should definitely be seen through the prism of the country’s sometimes volatile past.

While most of the world is currently dealing with inflation, many Brazilians remember hyper-inflation, which reached its apex in the 1980s and ‘90s. According to the World Bank, the rate of inflation reached 147% in 1986, and 228% in 1987. And it got even worse in the early 90s. There have been times in Brazil’s fairly recent past where price tags at retailers changed on a daily basis, and some stores gave up on putting price tags on goods at all. That is not what’s happening now – as of August, Brazil’s annual 8.7% inflation rate is on par with the US, at 8.3% – but for Brazilians who’ve lived through hyperinflation, seeing prices rise again has emotional and practical effects.

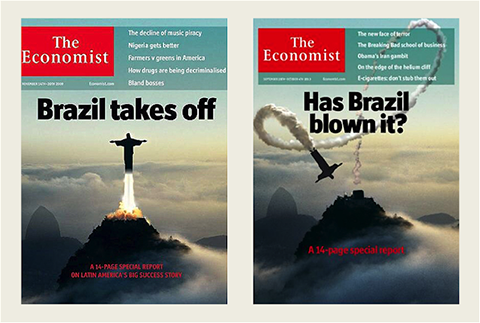

In fact, it’s not a coincidence that several contributors to this Spotlight mentioned two contrasting covers from The Economist that were only four years apart. One, from 2009, shows Rio de Janeiro’s famous Christ the Redeemer taking off like a rocket, and the other, from 2013 shows Him crashing to the ground.

It’s also a country that has had more than its share of political turmoil, suffering through an ongoing series of impeachments, imprisonment and controversy. As Brazil heads into its presidential elections next month, with the two top contenders being controversial right-wing current president Jair Bolsonaro and former left-wing president Luis Inácio (Lula) da Silva (who served a jail sentence after his presidency), Brazil is on edge, deep in the political polarization that has affected other countries, people, and also, brands.

These situations are affecting Brazilian consumers in obvious, and not so obvious, ways.

A focus on spending less – and on nostalgia

With approximately 74% of the population reporting finances are a primary worry, WGSN’s Mirela Dufrayer notes in her article, consumers are taking logical steps toward improving their finances. Research from McKinsey and Scanntech found both rampant brand-switching and a commitment among Brazilians to buy cheaper goods, such as private label products.

This isn’t great news for brands, but as Dufrayer notes, consumer needs can increase ways in which brands can be relevant. With Brazilians concerned about issues such as social disparity and food insecurity, brands such as Nestlé are stepping up. The CPG brand launched its first social-issue focused product this year, and 100% of profits will go to a project seeking to transform Brazil’s favelas (slums).

Brazilians’ privations extend into areas including education and leisure, which are being put on pause by many because of cost. Brands can play a role here, too. Ame, the fintech for one of the country’s biggest retailers, has launched free technology classes that both fill the education gap and advance diversity, since lower-income classes and women are very underrepresented in Brazilian tech. “Converting your brand into something that can prove transformative for consumers can also safeguard it during this time of rapid change,” Dufrayer says.

But the comfort of frivolity is also playing a major role in how Brazilians are combatting volatility. Daniele Lazzarotto, of the brand consultancy Cordao, reports Brazilians are reveling in nostalgia, in a trend that has been described by the online creative community WePresent, as “Comfort Culture.” This is being expressed through the renewed popularity of some 1990s telenovelas – the comfort comes from already knowing the plot.

This makes sense in a country where interest in film and cinema is the no. 1 interest, according to data from GWI featured in this Spotlight’s infographic. While 49% of the global population cites this as a top interest, in Brazil, 78% do.

The nostalgia trend doesn’t stop with what people watch. Lazzarotto notes there has also been an explosion in nostalgia-centered products, and even as Brazilians watch their wallets, these products are flying off the shelves. The beauty brand O Boticário’s collaboration with bubble gum brand Bubbaloo on a bubble-gum scented line of soaps and cosmetics sold out in just one day.

Frugality and nostalgia don’t have to be at odds with one another. “While brands should be helping people to navigate these difficult times with purposeful efforts … they can simultaneously find ways to celebrate and elevate the good memories of the past,” Lazzarotto says.

Brands are involved in politics, even if they don’t want to be

Especially as the presidential election looms, brands often find themselves in the political cross-hairs. But as articles for this Spotlight from the Brazilian agencies GUT and Talent Marcel point out, the choice for brands isn’t whether they should be involved, but how to move forward once they are. The brutal effects of “cancel culture,” fake news and bitterly divisive online communities, which look for everyone to take a side, are making it nearly impossible to stay above the political fray.

GUT advises that one safe space for brands is simply to encourage people to make their voices heard. Burger King in Brazil has taken this approach for some time, and this year is offering discounts to people who show their voter registration card at the moment of purchase.

Talent Marcel notes the benefits of embracing cancel culture, arguing that finding passionate communities that fit with a brand’s values – even if they turn off some – allow them to become part of a passionate sphere of influence. The key is “to understand which ecosystems fit its purposes and objectives, thus creating a solid and coherent positioning and, therefore, causing the desired impact.”

How Brazilian optimism, and the World Cup, are intertwined

Despite volatility past and present, there is an underlying optimism to Brazilian culture, and every four years, that optimism is expressed in the form of the World Cup, which fortunately is only months away.

Even though by then the election will be in the rearview mirror, to some extent polarization has hit this unifying event too, as the retailer Havan has co-opted the iconic football jersey – or Amarelinha, as it is known – as a symbol of support for Bolsonaro. (No, its marketing is definitely not taking the safer route of Burger King.)

But no matter what side of the political coin Brazilians fall on, they have similar attitudes toward the World Cup, and it’s that – of course! – Brazil is destined to win (even though the country last won it 20 years ago). Felipe Soalheiro of Effect Sport explains, “Not to sound pretentious at all, but Brazil is the only country that ‘loses’ the World Cup, as if it had always been our God-given right to own it, to make it only ours to lose.”

He continues, “This feeling of World Cup ownership in Brazil is why the best marketers in the country are the ones that share the belief that it is our destiny to win, a belief that extends way beyond the tournament itself.” The most recent example was 2002’s effort by Brahma beer, which featured a multi-city champions’ parade, forever associating the beer with World Cup victory. (Leading up to the World Cup this year, it’s taken on the burden of making the Amarelinha once again a symbol of Brazilian unity.)

Brazil, on the way back, again

Whatever the outcome of the World Cup, Brazil’s sense of optimism isn’t just about the tournament, and transcends current concerns about the economy. There are sound reasons for that. Even now, the country’s economy continues to progress in significant structural ways, becoming more modern and a better place for entrepreneurship than it was decades ago.

Renato Ribeiro, the CEO of the financial automation software start-up iugu, sees this clearly from where he sits. His company, which is backed by Goldman Sachs, helps smaller companies with tasks like billing and invoicing that didn’t have access to this kind of thing in the past, when the big banks ran every aspect of how money flowed. Similarly, companies such as Nubank are making it possible for more Brazilians to have such first-world basics as checking accounts.

In this interview, he explains that despite the country’s reputation for volatility, “Brazil is never that bad – never that good. It’s just a normal place that is better than yesterday.”

Read more in this Spotlight series

iugu’s Renato Ribeiro on how Brazil continues to open up its economy, and the role financial services play in making that happen

Renato Ribeiro

iugu

Budget-conscious, stressed out, Brazilian consumers require brands to take new approaches

Mirela Dufrayer

WGSN

To deal with uncertain times, Brazilians are embracing nostalgia, supporting local brands, and being more careful about what they buy

Daniele Lazzarotto

Cordão

I believe that we will win: How brands can successfully tap into Brazil's World Cup optimism

Felipe Soalheiro

Effect Sport São Paulo and SportBiz Consulting

The brighter side of “cancel culture”: Its ability to construct real connections between brands and people

Chimene Demski, Luiza Monteiro, Gabriela Soares, Camila Massari, Felipe Pádua, Rafael Salgado, and Gabriel Azevedo Lopes

Talent Marcel

Brands and political positioning in a polarized Brazil

Gisele Bambace, Amanda Agostini and Fernando Ribeiro

GUT

Brazil by the data: Its population, ad spend, media consumption and consumer behavior

Spotlight infographic

WARC and GWI