The #StopHateForProfit protest may signal the start of a wider clean-up of the digital media ecosystem, and a greater brand intolerance for the darker corners of the web.

Throughout the coming month, Facebook plans to run a series of webinars offering advertisers advice on how to use its platform during the Christmas period (more details here, if you’re interested). It speaks volumes for the confidence of the company to be planning that far ahead when it is currently grappling with its biggest advertiser revolt to date.

Black Lives Matter

This article is part of an ongoing WARC series focused on educating brand marketers on diversity and activism, in light of the recent progressive steps made with the Black Lives Matter movement.

The trickle of brands vowing to freeze ad spend with Facebook as part of the #StopHateForProfit movement has become a tidal wave: where Unilever, Starbucks and Coca-Cola first trod, brand owners including Ford, Adidas and HP have followed. For some, like Mars, the hiatus in social ad investment has been extended to include other platforms, including Twitter and Snapchat.

As commentators (including WARC Data) have pointed out, the collective action is unlikely to make a huge dent in Facebook’s bottom line. In many cases, the suspension is time-limited to a month, or only impacts US marketing spend, and Facebook will be hoping the boycott will be long forgotten by the time the festive season rolls around.

However, the growing consensus that Facebook must do more to curb hate speech is likely to have lasting consequences.

No longer just a provider of ‘digital plumbing’

It is worth pointing out, of course, that Facebook has announced a raft of measures to placate those that worry about its role in spreading hate and misinformation.

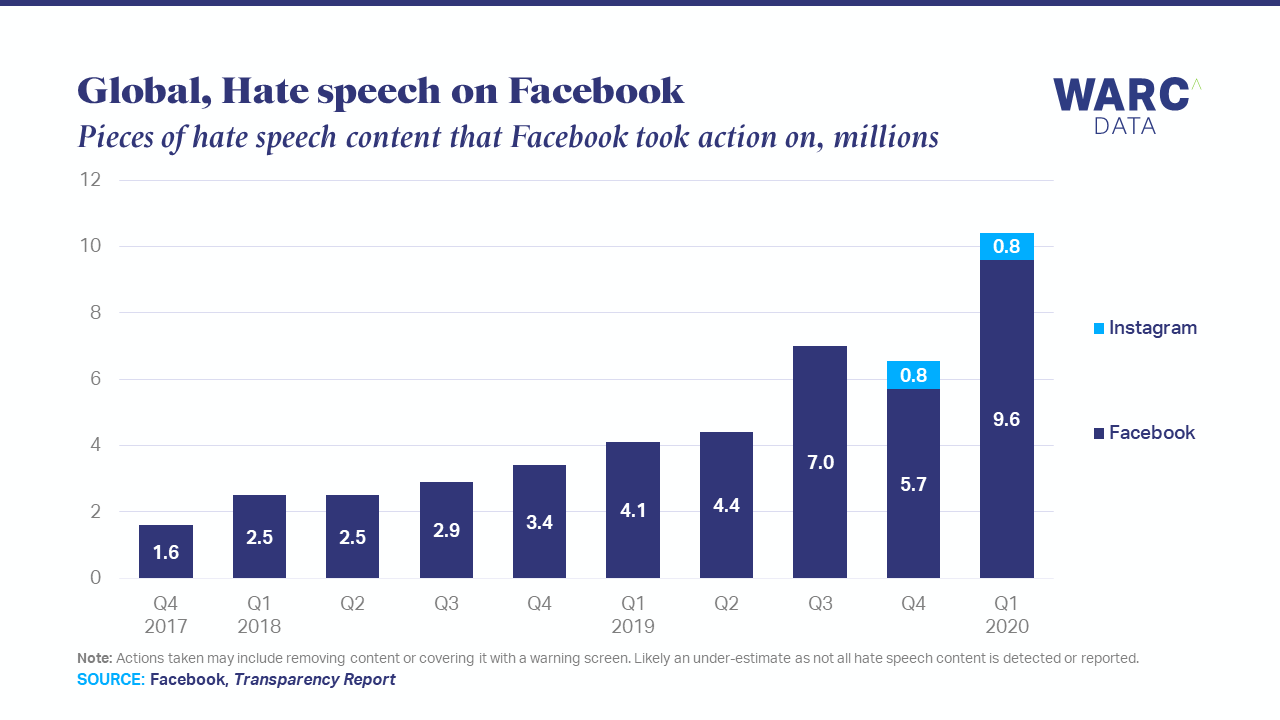

Facebook’s 35,000-strong moderation team now removes millions of instances of ‘hate speech’ each month (see below), while CEO Mark Zuckerberg places high hopes on machine learning as a long-term solution to the issue. The company also now promises to recruit experts on identity-based hate to help users who have been targeted because of “specific identity characteristics”, and it will refund brands when ads run in videos or in instant articles that violate its policies.

Nevertheless, a chasm remains in rhetoric between the two parties. Where Zuckerberg insists Facebook must stick to its “democratic traditions”, critics like #StopHateforProfit speak in much stronger terms, demanding the removal of all groups advocating, among other topics, white supremacy and climate denialism.

Facebook’s credits its success with its openness to all two billion-plus users, no matter where they live, how much they earn or who they support in the ballot box. Its platform reflects society – warts and all – and, besides, a tech company has no place setting the terms for political discourse.

To use a crude analogy, anyone of requisite age can walk into a pub and buy a beer. If they happen to imbibe too much of said alcohol and issue a few offensive utterances, well, that is unfortunate, but isn’t the fault of the pub landlord. On the other hand, if they become aggressive or incite violence, then the proprietor has a responsibility to act to protect his or her other customers.

An article published this week by Nick Clegg, the social network’s vice-president of global affairs and communications, insisted that Facebook “holds up a mirror to society”, and that it “does not profit from hate”. He added: “Ultimately, the best way to counter hurtful, divisive, offensive speech, is more speech. Exposing it to sunlight is better than hiding it in the shadows.”

Unfortunately for Facebook, the trouble is that much of the world disagrees.

Correlation or causality?

A schism has opened between those who agree that online hate speech is a reflection of the sad reality of racism and prejudice in society, and those who argue that Facebook has a pivotal role in causing the spread of those offensive ideas.

Critics contend that, rather than reflecting society’s ugly streak, it is the very algorithms and sharing mechanisms that make Facebook’s ad products so effective that are responsible for souring public debate. Some, including Rob Norman, ex-chief digital officer at GroupM, argue that Facebook must “add friction to the system” to ensure a “safer” environment for businesses and users.

Advertisers want Facebook to clean up its act and to become a ‘quality media environment’ by better policing the content being shared on its platform and removing the nasty fringe that has developed as a result of previous non-interventionist policies, rather than simply hiding the most hateful of content from users’ and brands’ eyes.

Speaking to WARC last year, Jon Steinback, Facebook’s director of product marketing for EMEA and global channels, said that the social network is helping advertisers to understand their safety “tolerances” – rather than the hygiene factor of “safety” – and the types of content they consider to be unsuitable for their brand or category.

In light of the protests sweeping the world in support of social and racial justice, advertisers are now re-thinking their tolerance in the context of entire media platforms and ecosystems, and not just content adjacency. Agency networks like IPG Mediabrands are launching new frameworks to help brands to create “responsible media” plans, for example.

Tolerance no longer relates to an article or video espousing unpalatable opinions and untruths; it now pertains to the website, app or social network on which that content is being hosted.

First Facebook, next the whole media landscape

Those defending Facebook point out that it is by no means the only social network to have an issue with hate speech – a point one can quickly verify with a brief wade into the cesspits lurking in the comments sections on sites ranging from YouTube to Reddit.

Facebook has become a rumpled piñata for commentators on both the left and right of the political spectrum to swipe at with abandon; Zuckerberg the pantomime villain at the heart of the story, waiting for brands to be lured back into his lair. As such, brands can feel relatively confident that their boycott is unlikely to offend either side in America’s fractious culture wars.

The boycott also offers marketers the chance to show that they are serious about making tangible changes in the wake of the awful circumstances of the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, and are responding to demands that corporations help to end systemic racism in the US and beyond.

However, to create truly meaningful change, brands must reappraise their tolerance across the media landscape. This means a radical overhaul of digital media buying, and a more intolerant approach to the deeply flawed programmatic trading system that still to this day sees advertisers chasing audiences into some pretty dark corners of the web.

The Facebook ad boycott will most likely be forgotten come Christmas, despite the impossibility of the task of policing 100 billion pieces of content each day. The platform is too important to many advertisers from an effectiveness perspective. But if collective action forces digital media owners at large to tackle hate speech, then some good will have come of it for both consumers, brands and civil society alike.