Our industry is in love with positive emotion. But brands operate in an increasingly complex socioecological context where emotion is only part of the story. It’s time to adopt approaches that enable people to be more intentional and conscious about what they buy, says Ian Murray, co-founder of Burst Your Bubble.

“I'm shocked at how irrational it (emotional advertising) makes us out to be. It suggests that human preferences can be changed with nothing more than a few arbitrary images. Even Pavlov's dogs weren't so easily manipulated.”

(Kevin Simler, Ads Don’t Work That Way)

Radio 4 was murmuring in the background when I sat down to write this column. I’d already decided to write about the fallacies that drive how marketers think about and use ‘emotion’ in advertising. Then Women’s Hour caught my ear.

They had an interview with Chioma Nnadi, the new Head of Editorial Content for British Vogue. She was being challenged about the damage that the fashion and beauty industry is doing to the environment, e.g:

- Of one hundred billion garments manufactured per year, 30 billion don’t make it to shops and are incinerated or go straight into landfill!

- Fashion contributes 8% of the world’s greenhouse gases, and

- Nine percent of microplastic pollution in our oceans.

Confronted with the evidence, Nnadi was keen to emphasise the importance of ‘supporting the brands who are doing the right thing.’ Above all, she stressed, ‘it is really important to be intentional about what you buy’…

Of course, this is also a familiar narrative in ad land. ‘Intentionality’ is central to the idea of ‘conscious consumerism’ and the feel-good stories that marketers tell themselves about ‘purpose.’ But marketers are also obsessed with ‘System 1’: i.e. the idea, picked up from Daniel Kahneman’s blockbuster, that effective advertising needs to appeal to people’s dependence on intuitive and automatic modes of thinking. I’ve written before about the pitfalls of this ‘emotional turn’. Decades of diverse scholarship that we now brand under the catchall ‘behavioural science’ has been reduced to a series of pejorative soundbites about people being slaves to their emotions and ‘biases.’

What fascinates me is that few people in our industry see the fundamental contradiction in these two dominant marketing narratives. Or how resolving this contradiction may hold the key to the commercial and social impact marketers seek.

In March, experts gathered at the Economist’s Sustainability Week events emphasised that the ‘say-do gap’ is as wide as ever. Much of the blame for the lack of progress focused on brands and their failure to support people in making better choices.

Closing the ‘say-do gap’ (on sustainability or any other goal) depends on the amount of thinking people put into it. But brands' over-reliance on System 1 strategies means they are doing little to encourage the kind of conscious and, yes, rational decision-making that is necessary to drive real behaviour change around the world’s most pressing social and ecological challenges.

The challenge for marketers is that their story about emotion and System 1 is partial and out of date. It hasn’t kept up with the science or with the increasingly complex socioecological context in which brands now operate. As long as ‘emotion’ remains the answer to every question in our industry, ‘conscious consumerism’ will remain little more than an elusive ideal.

Here are a couple of thoughts/provocations on how we can redress the balance and move towards a more holistic view of real-world decision-making.

1. Behavioural Science was never about System 1

As per the quote from Kevin Simler at the top of this piece, one of the big problems with the ‘emotional inception’ model of advertising is that it denies people’s agency. But preserving human agency has always been a key concern in the social sciences. And there is a growing body of scientific evidence that seeks to reclaim human agency from the worst excesses of the ‘nudge’ theories that have played such a dominant role in our industry’s devotion to System 1.

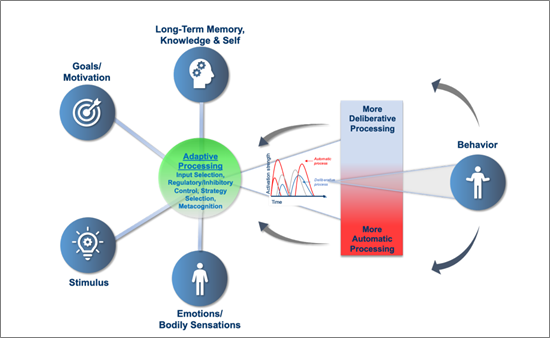

As IPSOS outlined in a series of recent papers, the latest scientific evidence makes two important advances that challenge the current orthodoxy around emotional inception in advertising (Figure 1):

- Contrary to ‘dual process’ theories of decision-making (i.e. System 1 v System 2) automatic and deliberative decision-making are not dichotomous and mutually exclusive.

- There is a regulatory process (System 3) that enables people to adapt their responses (i.e. more or less emotional or rational) depending on decision contexts.

People employ highly adaptive and diverse decision strategies depending on a wide range of factors including their personal goals and motivations, knowledge, and experience. It should be clear how thinking more holistically about System 3 is critical to our future understanding of how advertising works and indeed its role in making a positive contribution to society. System 3 gives people back their agency and a degree of control over decision-making. System 3 also puts deliberation back in the mix and provides advertisers with a far broader toolkit to support conscious consumerism.

Figure 1 IPSOS Dynamic Decision-Making Model

2. Marketers need to get comfortable with ‘emodiversity.’

Of course, System 3 does not negate the role of emotion. Emotion still plays a key role in people’s highly adaptive real-world decision-making. But marketers are also limiting their impact by adhering to a reductionist view of emotion and the diversity of emotions that are in play in real life.

In ‘The Secret to Happiness: Feeling Good or Feeling Right’ (2017) Tamir and colleagues challenge the conventional view that being happy depends on experiencing pleasant emotions.

Across cultures, their research found that happier people were those who more often experienced emotions they wanted to experience, whether these were pleasant (e.g., love) or unpleasant (e.g., anger). Contrary to the standard narrative in advertising, these findings suggest that happiness involves experiencing emotions that feel right, whether they feel good or not.

Embracing emodiversity provides another potential route to closing the ‘say-do’ gap. Marketers are obsessed with making people feel good about sustainability. But the key to real behaviour change around this (and many other issues that marketers champion) may be in helping people to feel emotions that are appropriate and congruent with the issues being featured in marketing communication.

In the Handbook of Affective Science, Johnathan Haidt describes anger as ‘the most underappreciated moral emotion’. From an evolutionary perspective, anger is recognised as a vital mechanism for overcoming obstacles and helping humans achieve their most fundamental goals (i.e. survival and reproduction). Viewed in this context, people should be angry and scared about our socioecological crisis. People also think deeply about the things that matter to them.

Behavioural Science has never been all about System 1 and positive emotions. In the real world, System 1 gets us fast fashion and lots of other unsustainable behaviours. It can’t be the whole story for marketers who are serious about making a difference.