WARC from Home is a new series to help subscribers brush up on the essentials of marketing during the COVID-19 lockdown. Find all WARC from Home content here.

Every week we’ll guide you around the latest thinking on a key topic, pointing you in the direction of must-read articles, seminal research papers and essential webinars, to ensure you are top of the class when we all finally return to office life.

This week we’re taking a close look at brand equity – namely the added value a brand can give to a product or service to help to fuel business growth. We explore the origins of equity modelling, how brands can be measured, and the impact that marketing can have on brand equity.

What do you mean by brand equity?

In the years after the Second World War, advertising luminary including David Ogilvy liked to talk about ‘brand image’ – a mostly vague term, dismissed by many in the research field as lacking substance. This all changed in the 1980s, when a succession of acquisitions in the CPG category revealed that companies were willing to spend vast sums on brands.

The idea of brand equity emerged from the finance world, used by investment bankers as a method of acquisition accounting, and by accountants as a means of reducing corporate tax bills. It has since become a crucial way for marketers to prove the long-term benefits of investment to potentially sceptical boardroom colleagues.

Yet, while most advertisers would agree on a rough definition of brand equity – the value created by having a well-known brand name that can influence consumer behaviour – it is tricky to quantify, and there remains no universally accepted form of measurement.

Essential reading:

- Why do brands matter? By Jerry W. Thomas (Admap Magazine, 2018)

- Brands and the CEO: What marketers need to know and do by Patrick Barwise (Market Leader, 2016)

For a deeper dive

- What is brand equity anyway, and how do you measure it? By Paul Feldwick (International Journal of Market Research, 1996)

I still don’t get it.

That’s understandable. Definitions of brand equity – and how to measure it – differ depending on who you listen to.

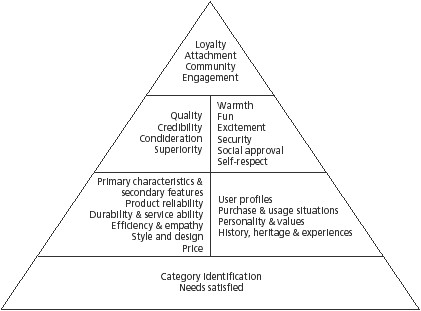

For instance, two prevailing (and contradictory) models were proposed in the 1990s by David Aaker and Kevin Keller. Aaker identified brand awareness and associations, perceived quality and loyalty as key dimensions of brand equity. In comparison, Keller’s ‘CBBE’ model defined equity as the effect of brand knowledge on consumer response to brand marketing (see Keller’s ‘CBBE pyramid’ below).

Renowned planner Alan Cooper, meanwhile, argued that brand equity has three key components:

- Brand description: the brand’s image, its distinctiveness, and the esteem in which it is held by consumers.

- Brand strength: the brand’s prominence and relative dominance within a category (eg awareness, penetration, share, loyalty).

- Brand future: a brand's ability to survive changes in legislation, technology, retail structure and consumer demand, and its growth potential (eg niche to mainstream, or local to global).

Essential reading:

- Brand equity - a lifestage model by Alan Cooper (Admap Magazine, 1998)

OK, so you’re talking about brand valuation?

Sort of, but not entirely. As the business world became accustomed to the idea of measuring the intangible value of a brand, a host of proprietary models emerged from companies including Interbrand, Brand Finance and Millward Brown (BrandZ) to quantify and compare brand value.

David Haigh, founder of Brand Finance, described brand valuation as “the best thing to ever happen to market research”. However, these models can produce wildly differing outcomes: as observed by Ogilvy’s Joanna Seddon in 2012, Interbrand’s valuation of the Apple brand came out at $77bn, 58% less than BrandZ’s $183bn.

Ebiquity takes a slightly different approach, using econometric modelling to assess the impact of brand equity on long-term brand performance. This reflects a longer-term trend towards assessing brand equity in terms relevant to marketers and agencies, and not just accountants. However – as recently outlined by US academic David W. Stewart – there remains an urgent need for marketers to place clearer financial value on the returns delivered by intangible assets such as brands.

For a deeper dive:

- The Brand in the Boardroom: Making the case for investment in brand by Joanna Seddon (2013)

How do I build brand equity?

The benefits of brand equity are obvious. Strong brands can command higher prices, withstand economic adversity and improve ROI. High brand loyalty and awareness can reduce marketing costs, and help achieve success for new products introduced as brand extensions.

However, this strength cannot be achieved overnight. Equity creation is a gradual, long-term process which involves strategic marketing investments to improve brand performance against measures such as consumer awareness, salience and favourability.

Advertising clearly plays a key role in maintaining and building brand equity, but so too do other marketing levers, such as customer experience, innovation and events. Some experts including former Procter & Gamble CMO Jim Stengel have argued the value of a central purpose or cause in helping to develop equity. Conversely, tactics such as promotions and discounting can have a negative impact on brand equity.

To monitor progress, Kantar’s Josh Samuel recommends a tracking programme consisting of a set of annual or six-monthly equity KPIs. Singapore-based real estate site PropertyGuru increased media effectiveness by the adoption of a continuous measurement approach to brand equity, while PepsiCo measured brand equity to find an optimal pricing strategy for its snack brands in India.

Essential reading:

- Advertising and brand equity by Andy Farr (Admap Magazine, April 1996)

- Why marketers must establish KPIs that grow brand equity by Josh Samuel (Admap Magazine, April 2017)

For a deeper dive:

- Secrets of profitable brand growth (WARC Webinars, February 2016)

What if I don’t bother?

The story of Lacoste provides a cautionary tale for any advertiser neglecting brand equity.

The French clothing manufacturer, known for its shirts with a signature crocodile logo, became popular with US consumers from its entry into the market in the 1950s – so much so that it attracted the interest of General Mills, which acquired the license to manage and market the Lacoste brand.

In the mid-1980s, in order to further grow sales, General Mills lowered prices and expanded the distribution from strictly high-end stores to discount outlets. The short-term outcome was predictably an immediate revenue increase. However, within a number of years, the brand lost its prestige image and profit margins flattened.

Only by raising prices and limiting distribution to high-end retailers were Lacoste’s subsequent management teams able to revive brand equity and restore margins.

For a deeper dive:

- Long-term effects of marketing actions by Michael Hess (2016)

We hope you enjoyed this lesson and found it useful. Please do share any feedback, and get in touch with the WARC team if you would like to find out more.