Elon Musk’s decision to change Twitter’s name to X has damaged overall brand sentiment and usage intent, new figures have shown.

Tracksuit, the brand tracking company, surveyed 3,172 consumers in Australia, the UK and US about this rebranding, and offered a bit of good news to the social media platform, as only 8% of contributors were unfamiliar with the recent alteration in its name.

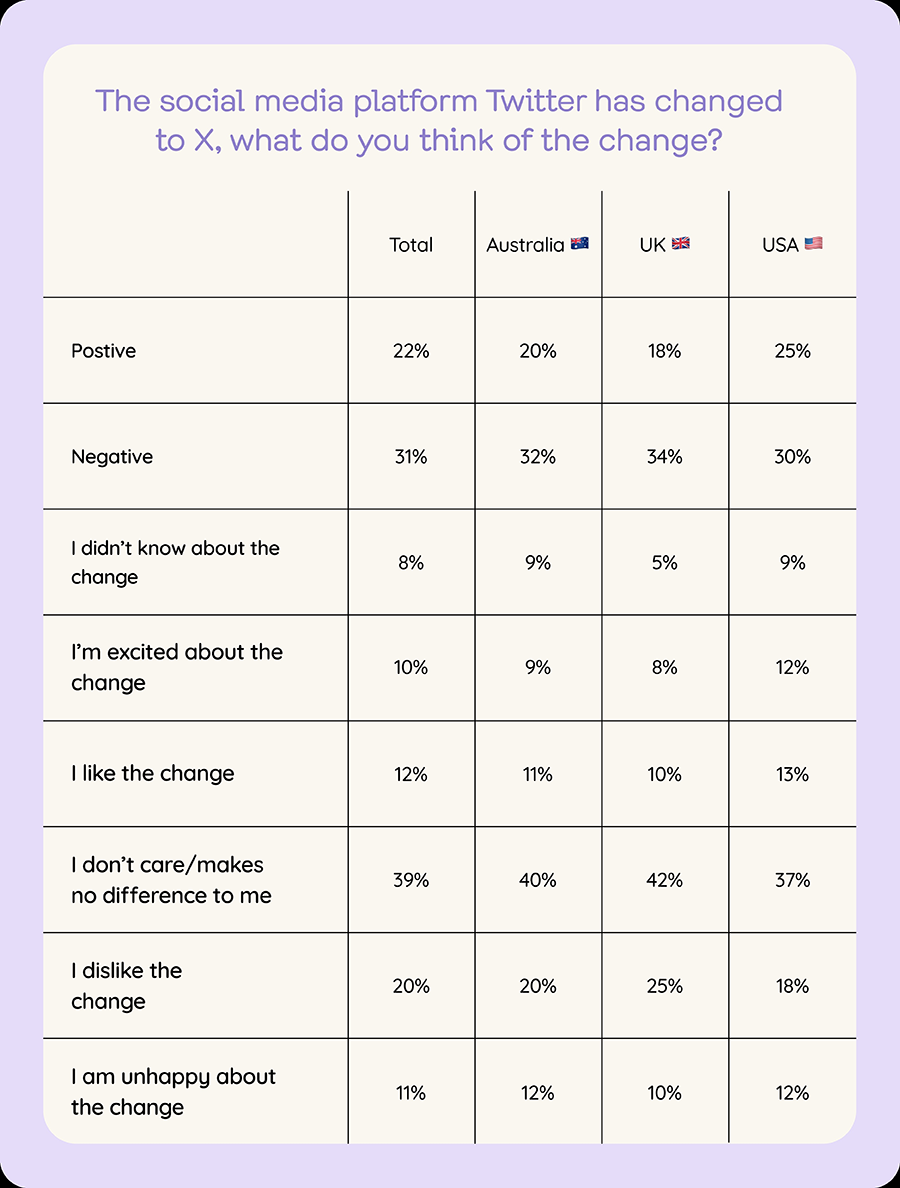

And the bad news? It found that 31% of respondents had a negative reaction to this change, versus 22% with positive views – a net gap of nine points. Drilling down further into the specifics revealed that 12% of the panel “liked” the rechristening to X and 10% were “excited” by it; some 20%, by contrast, “disliked” the change and 11% were “unhappy” with it.

Thirty-nine percent of the sample, when discussing the same topic, agreed they either “don’t care” or it “makes no difference to me” – an indifferent audience which could potentially be swayed either way about the X brand depending on its strategy going forwards.

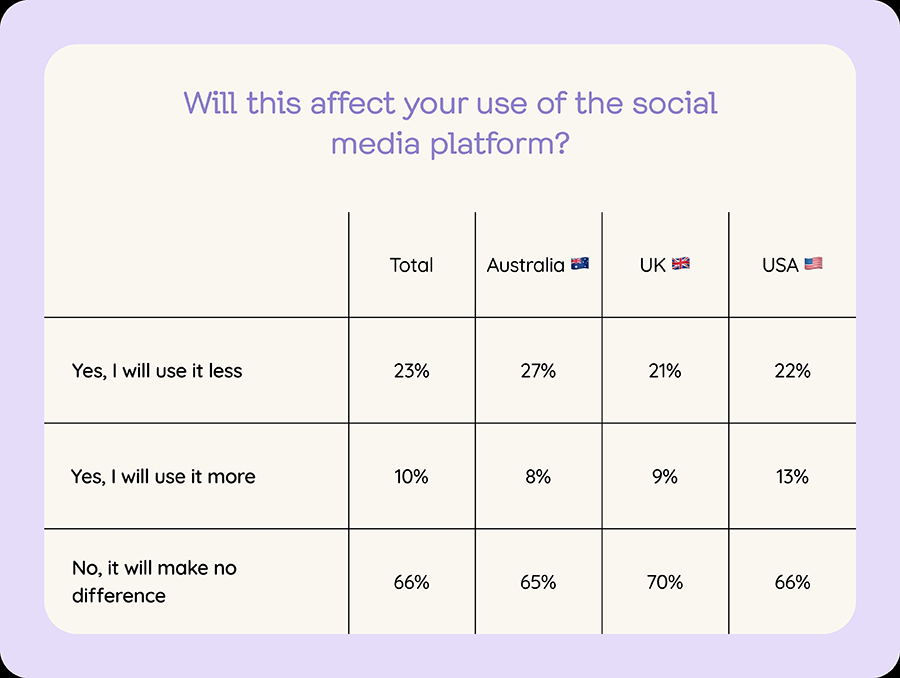

Tracksuit also reported that 23% of participants said they would use the platform less following the rebrand, versus 10% who anticipated increasing this activity. Two-thirds of those polled suggested their behavior will be unchanged, leaving another net decline for the brand.

And recent data has corroborated Tracksuit’s insights: X’s web usage and app downloads have both declined, while user churn has risen.

Brand value is hard won, quickly lost

Rebrands can be implemented for a variety of reasons: A strategic pivot, entering a new industry, responding to a corporate crisis, and so on.

In the case of Twitter, however, part of the motivation appears simply to be fulfilling a long-held desire of Musk – who acquired the platform in late 2022 – to run a brand named “X”.

Beyond that, the sudden announcement epitomized Musk’s haphazard approach to operating a cornerstone of the social media ecosystem, which quickly led many advertisers to pull back from the service as they worried about reduced content moderation and platform instability.

An optimistic spin on the rebrand is that it creates new space for a transformation in user expectations, in line with a stated goal to develop an “everything app” that, in the words of Linda Yaccarino, X’s CEO, will be “centered in audio, video, messaging, payments/banking” and deliver “a global marketplace for ideas, goods, services, and opportunities.”

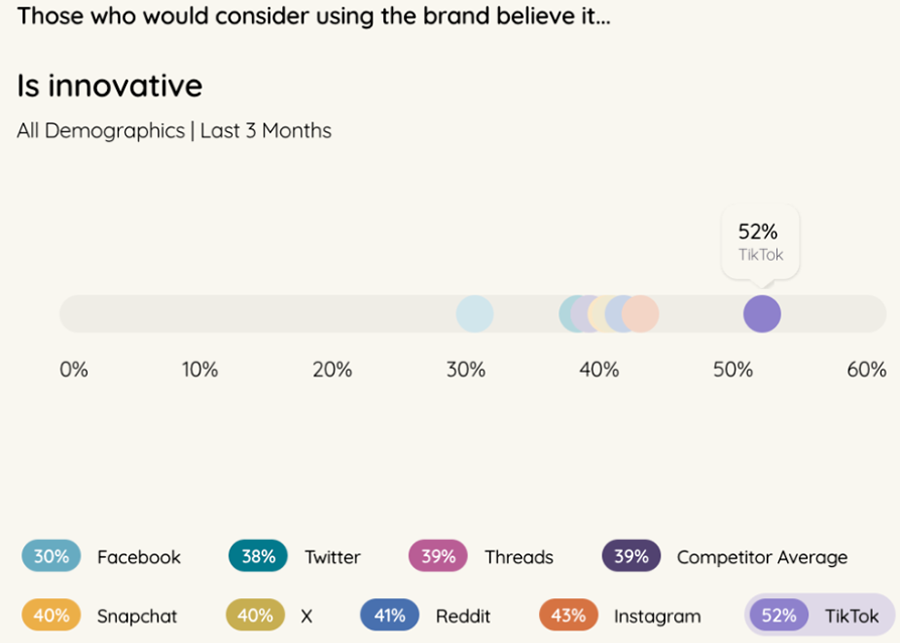

Data from Tracksuit’s always-on US consumer panel offers (extremely) qualified support for this notion, as X outperformed Twitter on perceptions of being “innovative” among people who would consider using these brands. The gap, however, was just two percentage points – and both X and Twitter lagged behind Reddit, Instagram and TikTok on this metric.

Simultaneously, the rebrand wiped out considerable equity that had been accrued over many years by one of social media’s best-known properties. Prior to the rebrand, one study estimated that Twitter’s value had already dropped by 32%, or $3.2bn, year on year following Musk’s takeover; after the rebrand, industry-watchers pegged that figure at between $4bn and $20bn.

One key contributor to that outcome is the demise of numerous distinctive assets (also sometimes known as “fluent devices”, and which are the foundations of a brand’s enduring strength) that are – or, at least, were – inextricably connected with Twitter.

The most visible example: Its blue bird logo was a widespread feature on brand and media websites as a link to their Twitter feeds, while hanging decals let physical stores and small businesses show they wanted to engage consumers in the digital world. (X’s logo, by contrast, has been called “optically misaligned” and compared with an “authoritarian symbol”.)

Some of Twitter’s brand assets even held a place in our shared online vocabulary: The term “tweet” started life as the name for a user post, then evolved into a verb; its hashtags became a common form of expressive shorthand; and platform-specific neologisms like “tweetstorm” – a barrage of posts from a user in a short time – made it into in Merriam-Webster’s dictionary.

On-site aspects of Twitter’s brand architecture have been upended, too: Its blue checkmarks, for instance, were once a company-assigned indicator of a user’s expertise or fame. Now, thanks to the “X Premium” feature, they are given to any subscriber paying $8 a month – users who also receive heightened prominence for their messages.

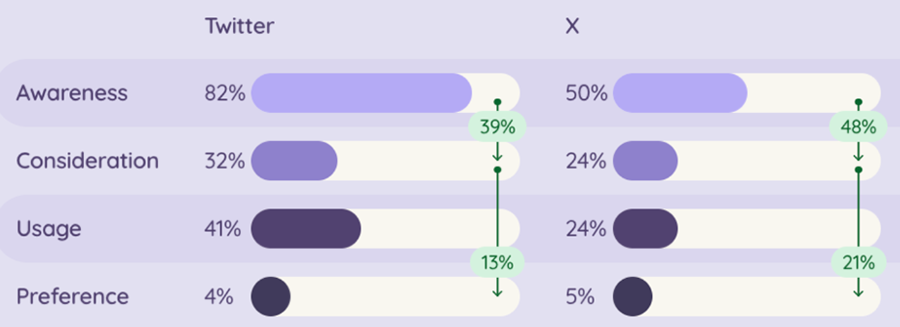

Figures from Tracksuit’s US panel offer a fuller insight into what this destruction of brand equity means across several metrics, as X trails Twitter for brand awareness, consideration and usage. The only plus? A one-point gain in terms of preference.

All rebrands, of course, will suffer a degree of pushback from change-resistant audiences. But they are, usually, the product of in-depth analysis, gathering rigorous insights, consistent messaging and a well-defined long-term vision.

Similarly, initial antagonism to the demise of Twitter can be expected to subside, and building equity for its successor would then ideally rest on the slow, careful work that underpins every strong, trusted brand. X, however, is still essentially a fuzzy concept – aside, perhaps, from vague ambitions and being enmeshed with Musk’s whims and caprices.

Leaders as a brand asset (or not)

In the tech industry, more than any other, chief executives (CEOs) have an outsized status in relation to the enterprises (and, by extension, the brands) they lead – think Mark Zuckerberg at Meta, Steve Jobs at Apple and Bill Gates at Microsoft.

Often, these CEOs are founders who are perceived as challenging the status quo. And rebranding Twitter might be intended to help Musk galvanize some of this disruptive spirit, roughly as he achieved when taking the reins at electric carmaker Tesla.

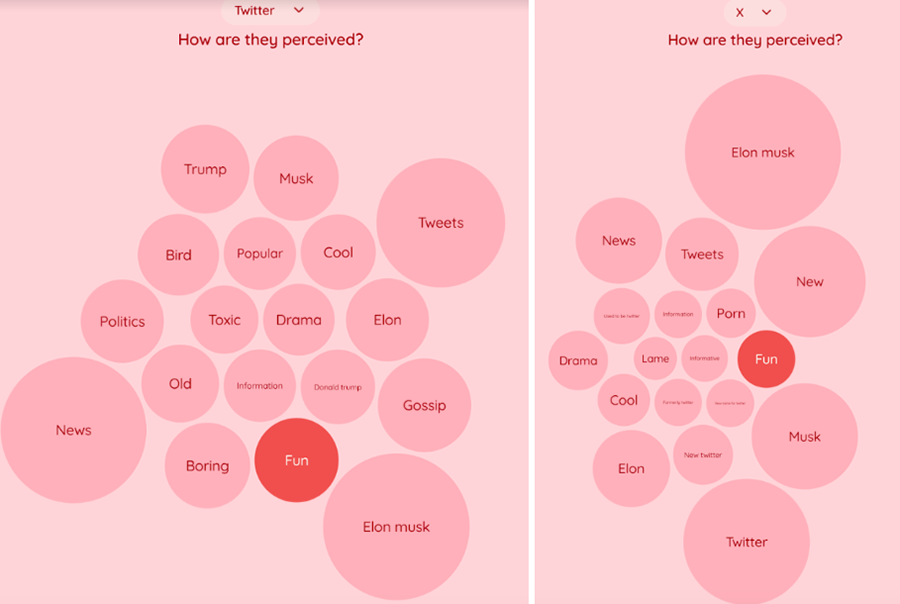

Although Musk hired Yaccarino as X’s CEO in May 2023 to take on the roles of executive chair and chief technology officer, he undoubtedly remains synonymous with X, far more so than with Twitter, as Tracksuit’s data covering brand perceptions in the US demonstrates. This means his actions exert a potent impact on the brand.

Given that backdrop, a useful proxy in understanding his role is to look at evidence which shows that achieving the right “fit” between a CEO and a brand can have positive effects – while CEOs who are seen as irresponsible generally achieve the opposite.

One study in the Journal of Advertising Research, for example, noted that CEOs have a brand – based on their personality, performance and leadership – that is distinct from corporate brands and product brand awareness. And, it discovered, on social media, the chief executive’s own brand image predicts advertising credibility.

Elsewhere, Brand Finance, the brand valuation consultancy, publishes an annual ranking of CEOs based on their “brand guardianship” – and Musk dropped out of its top 100 in 2023, having claimed 30th spot in 2022, due in part to his leadership at Twitter.

The social media platform’s travails have potentially delivered an unwanted halo effect for Tesla, too, as it has plummeted down a consumer survey of reputable brands. A Bloomberg poll among Tesla owners further confirmed that Musk’s public utterances were regarded as harming the automaker’s reputation.

Free for all?

The biggest social media platforms have built audiences through offering free access to users in exchange for seeing ads.

Recent subscription plans from Snapchat and Meta have looked beyond this approach and, last month, Musk suggested that Twitter may charge all users a “small monthly payment” – albeit without clarifying a dollar amount or a timeline for doing so. A test program is also charging new users in New Zealand and the Philippines a $1 fee.

A 2023 study in the Harvard Business Review revealed that paid-for subscribers to what is now “X Premium” were generally satisfied with the level of pricing. This viewpoint, it explained, was more prevalent among “college-educated, conservative, younger, male, and high-income users” – a cohort that seemingly fits in with Musk’s own political leanings.

This insight hints at a broader truth: Disentangling the consumer response to Twitter’s rebrand from the incessant conversation around Musk, and his scattershot approach to decision-making, has become a near-impossible task.

His online prominence and erratic style might appeal to a devoted legion of fans, but ultimately could alienate more people than they attract – as well as discouraging advertisers from returning to X if they believe it remains an unpredictable, or unsafe, environment for their brands.